Felix Draeseke: Chamber

Music

Music for Cello and Piano

|

New Repertoire for Cellists: Felix Draeseke's Compositions for Cello and Piano by Barbara Thiem |

|

| Related link: Read Udo Follert's Article on Draeseke's Music for 'Cello |

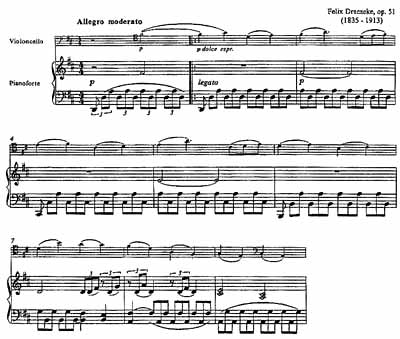

The cello sonata repertoire of the nineteenth century is quite limited. Although Elizabeth Cowling mentions 224 cello sonatas written during that period, only a handful are still played, and very few are available in modern editions [1]. The only sonatas cellists frequently play are two by Mendelssohn, one by Chopin, two by Brahms, one by Grieg, and one by Strauss. Sonatas occasionally played are two by Saint-Saëns and two by Fauré. Cellists are therefore lucky to live in a time when the oeuvre of the late nineteenth-century composer Felix Draeseke has been rediscovered. Among his most brilliant compositions are the works for cello and piano. Felix Draeseke (b. Coburg 1835; d. Dresden 1913) studied in Leipzig and Weimar. One of his teachers was Franz Liszt. From 1862 to 1876 he taught in Lausanne, Switzerland, and during that time he wrote two shorter pieces for cello. In 1884 he went back to Dresden where he taught at the conservatory[2]. In this period he wrote his Cello Sonata in D Major (1890). Fans and admirers of Felix Draeseke founded the Internationale Draeseke Gesellschaft of Germany in 1986 and its American branch in 1993. These organizations have helped in resurrecting the many compositions by Draeseke, and they have played an active part in financing performances, recordings, and publications of his works. An impressive list of works has been reprinted. Besides the large works-including requiems, masses, oratorios, and his Fourth Symphony-publishers have issued much of the chamber repertoire including two string quartets, the String Quintet Op. 77, the Clarinet Sonata Op. 38, the viola alta sonatas, and sonatas for piano. In the last year alone recordings have been released of the Clarinet Sonata and its violin version, the Piano Concerto in E-flat Major, the First and Third Symphonies, and the Funeral March in E minor. Like the two sonatas for viola and piano discussed in an August 1998 AST article, the cello compositions have been published by Wollenweber and recently recorded [3]. They include the magisterial Sonata for Cello in D Major, Op. 51 (1890) and two shorter cello pieces, the Ballade in B Minor, Op. 7 (1866) and the Barcarole in A Minor, Op. 11 (1872). After having written successfully in the style of his admired teachers and friends Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner, Draeseke made an unprecedented move. He endeavored to blend their Romantic style of writing with the seemingly incompatible Classical idiom of Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms. As a result, Liszt, Wagner, and their followers looked on him as a traitor. For the followers of Schumann, on the other hand, his music and harmonic language seemed much too progressive. The Cello Sonata Op. 51 exemplifies his success in blending the two styles and in creating a new and independent musical language that evokes feelings that are at once stirring and elusive. Draeseke is not just a highly competent craftsman. He is also more successful than most Romantic composers in striking the right balance between the particular tone qualities and amplitudes of cello and piano when they are played together. Even his two early works, the Ballade and the Barcarole, turned out as masterly duos. In the densest piano textures there is no danger the cello will not be heard. Both piano and cello writing are effective and idiomatic, often difficult, but always to brilliant effect [4]. Draeseke dedicated both the Ballade (1866) and Barcarole (1872) to the cellist Friedrich Gruetzmacher. Technically less demanding than the Sonata, they are perhaps on a level with the Brahms Sonata in E Minor, Op. 38. Both are expressive pieces, requiring a wide range of vibrato and bow colors. They will give students greater variety of repertoire, which now will no longer be limited to the Schumann and Fauré pieces commonly taught. The Sonata Op. 51 (1890), dedicated to Julius Klengel, was first performed by Friedrich Gruetzmacher. Both Klengel and Gruetzmacher were the foremost cello virtuosos of their day. The level of difficulty of the sonata compares best with Brahms's sonata in F Major, Op. 99, as well as the Strauss Sonata in F Major. Draeseke's Sonata is highly lyrical. It lies well on the cello, but has exposed high register in many places. There are three movements: Allegro moderato; Largo molto espressivo; and Allegro vivace con fuoco. The

first movement is reminiscent of the Brahms F Major Sonata's

last movement. The very melodic cello writing is largely on

the top two strings. The movement is in traditional sonata

form. It begins with a slow melody in the cello over a carpet

of piano triplets. When the piano takes over this theme the

cello continues to play in imitation with it; see Example 1:

The

development section of the first movement has an extraordinary

variety of key changes. The music sometimes seems to dissolve

into far away tonal centers. Shortly before the recapitulation,

E-flat major is established, a half-step higher than the main

key of D major that the listener expects at this point. Draeseke

resolves this dilemma in a very simple way in measures 161-163,

by changing the E-flat major into the Neapolitan sixth chord

of the main key. He thus creates a magical reemergence of the

beginning material. After a shortened recapitulation the movement

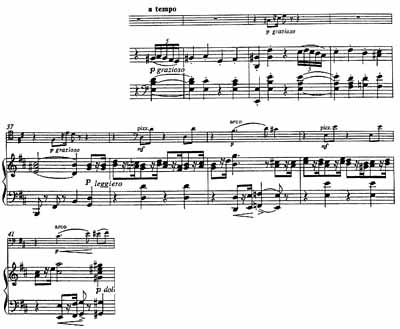

ends quietly and simply. The

second movement is in ABA form. The dramatic first part also

makes use of the lower register of the cello. (See Example

3.) It is in F-sharp minor and alternates with a flowing lyrical

second theme area in C major. The B section is monothematic

in D major and uses extreme dynamic tensions. It is a grazioso

in 9/8 and much faster than the A section. At the climax the

cello plays in a very high register, supported by the piano

in the way vocal parts are often written and reminiscent of

the Strauss Sonata in F Major. (See Example 4.) The A section

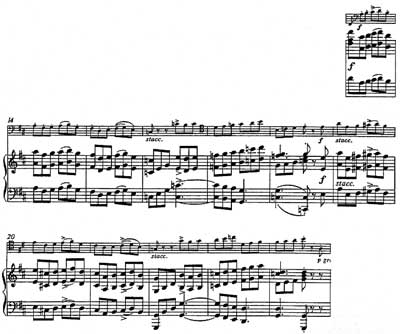

returns with a continual heightening of dramatic contrasts. The

last movement is a whirling rondo with many themes. It starts

with an introduction, working up to the complete theme statement

in measure 13 that is in unison between the instruments, with

octaves in the piano part; see Example 5: This short theme comes back in almost every possible key throughout the movement. The movement is extremely difficult for the pianist because of the many octave passages. It is highly rhythmical like the last movement of the Strauss Sonata. The C-sharp minor second theme is expressive and slow, exposed technically and poignantly lyrical in the high cello register. There is a surprise in the end-an impasse in which the first theme has spiraled to an abrupt end. Then, as from afar, the melody from the middle section of the second movement returns (m. 406), a piano espressivo which disappears into pianissimo. The movement finishes with an exuberant merry section. In the twentieth-century repertoire cellists have the Debussy Sonata and the Elgar Concerto, which fall under the influence of the Liszt-Wagner harmonic system. The Draeseke Sonata is the only work written before the twentieth century that is not in the Classical style, but composed with the new harmonic freedom inspired by Wagner. References Musical examples used by permission of the International Draeseke Society. This article originally appeared in American String Teacher (February 2002, pp 92-5). This web adaptation appears by permission of the American String Teachers Association with National School Orchestra Association, copyright 2002. For more information about joining ASTA with NSOA, go to www.astaweb.com. Barbara Thiem is a performer who also teaches cello and chamber music at Colorado State University and the University of Wyoming.

Ms. Thiem has held teaching positions at Iowa State University, the University of Texas at Dallas, and several universities in Colorado. At present she is also artist-in-residence at Colorado State University. She makes her home in Fort Collins, Colorado, and spends the summers with her family in Austria. She is an active performer as a soloist with orchestras and in solo and chamber music recitals and has been a member of the Dallas Piano Trio and the Mendelssohn Trio. Her concerts and recordings have taken her all over Europe, the U.S., and Canada. She has produced CD's of Bach's solo suites, cello and bass duos with Gary Karr, works by the 19th century composer Felix Draeseke with Wolfgang Müller-Steinbach, and cello and organ music with Robert Cavarra. her publications include the translation of Gerhard Mantel's Cello Technique, as well as several articles in the field of music and medicine. In the summer of 2001, Ms. Thiem was the co-director of the summer string festival at Musikakademie auf Schloss Ort, where she organized concert activities, taught and performed in chamber music concerts. Department

of Music |

| Related

links: Udo Follert's Article on Draeseke's Music for 'Cello (in German) Alan Krueck's Article on Draeseke's cello compositions (English/German) Draeseke's Music for 'Cello on AK/Coburg CDs |

|

| Draeseke's Cello music on CD: | |

|

AK Coburg DR 0002 [CD] Sonata for Cello and Piano

in D op. 51

Read Henry Fogel's review from Fanfare. |

|

|

Click on this icon

above [ |

|

[Chamber Music] [Orchestral Music] [Keyboard Music]

© All contents copyright by the International Draeseke Society

Born

and raised in Germany, Barbara Thiem came to the United States

for graduate studies in music at Indiana University where she

studied with Janos Starker and received her Master of Music

in cello performance and the coveted Performer's Certificate.

In Germany, Ms. Thiem studied with Siegfried Palm (Cologne),

a specialist in 20th century cello music.

Born

and raised in Germany, Barbara Thiem came to the United States

for graduate studies in music at Indiana University where she

studied with Janos Starker and received her Master of Music

in cello performance and the coveted Performer's Certificate.

In Germany, Ms. Thiem studied with Siegfried Palm (Cologne),

a specialist in 20th century cello music. The

cello sonata dates from 1890 and demands virtuoso ability from

its performers as well as an intimate understanding of its

shifting harmonies and intricate contrapuntal relationships.

The 1866 Ballade is a study in elegiac melancholy while the

Barcarole of 1872 is a classic example of the genre piece evoking

undulating waves and gondolas plying Venetian lagoons. The

selection of piano pieces shows a series of genre pieces which

at times transcend those boundaries through their sophistication

and difficulty.

The

cello sonata dates from 1890 and demands virtuoso ability from

its performers as well as an intimate understanding of its

shifting harmonies and intricate contrapuntal relationships.

The 1866 Ballade is a study in elegiac melancholy while the

Barcarole of 1872 is a classic example of the genre piece evoking

undulating waves and gondolas plying Venetian lagoons. The

selection of piano pieces shows a series of genre pieces which

at times transcend those boundaries through their sophistication

and difficulty.